I made a skirt out of my cloud storage

How to reclaim your data and feel the weight of a digital life

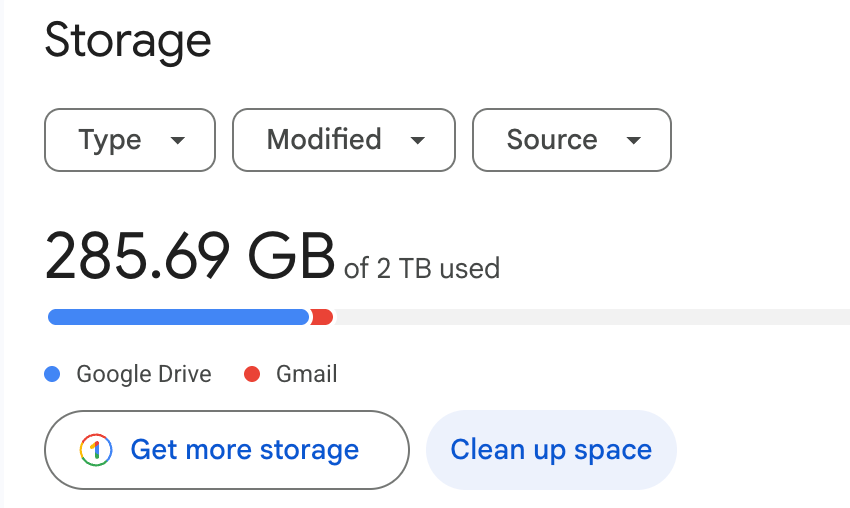

Every year, I spend roughly $371.76 on cloud storage.

My whole life lives on the cloud. My photos, heartfelt messages, emails to loved ones… every piece of my writing. The cloud —while intangible to most— seems more permanent than a hard drive. A USB can be lost. Hardware can weather. Right?

In 2015, I made a documentary about my late grandfather. It was one of the few truly intimate conversations I had with my classically stoic Asian grandpa before I lost him to dementia. I had uploaded the documentary to YouTube, thinking it would last my lifetime. But a few months back, when I returned to the unlisted link I had saved, I was greeted by an ominous “this media is no longer available” error message.

My heart dropped.

My one other copy lived on an ancient model of a MacBook, riddled with viruses from my adolescent torrent days. Being able to turn on the computer was itself a shock. In denial, I spent a week rifling through every dusty hard drive I could find in my childhood home — it was only when I managed to contact the organizer of a film festival that featured my doc all those years ago that I got a copy of this film. They, sensibly, had a formal archiving system.

The experience puzzled me: keeping things stored locally felt archaic, but storing things on the cloud also felt fragile. What if Google decided to pull the plug tomorrow?

I decided I needed to reclaim my digital footprint. I want to feel the weight of my digital life in my hands. I want to be in complete control of my memories.

What I gave up: cloud storage

How did I cope: local drives and a skirt made of USBs

Did it suck: 50/50

The fragility of the internet

80% of all websites on the internet are inactive. Link rot leaves all your data/content at the mercy of a business decision. MTV’s 30-year archive was recently taken down due to operation costs, and Google can nuke your entire life in the blink of an eye by erroneously classifying pictures you take of your child’s rash as ‘child pornography.’

People say the internet is forever. I don’t think it is.

The internet is vast. It’s a garden. A ‘dark’ forest, if you will. Every day a new tree is planted the same time an entire meadow wilts. While non-profits like the Internet Archive and Wayback Machine exist, the attitude towards preserving the digital world has time and again been compared to a daily burning of the library of Alexandria. I mean, who’s out here downloading their webpages like PDFs?

Everything online is constantly updating, so localized storage can never really keep up. To me, the .finalFINALfinal file name conjures a nostalgic yet visceral cringe. Besides, personal hard drives aren’t often cared for the same way as data centers, nor do they seem to last. What if we get rid of USB ports? What if the hardware deteriorates?

Hard drives don’t have to be perishable

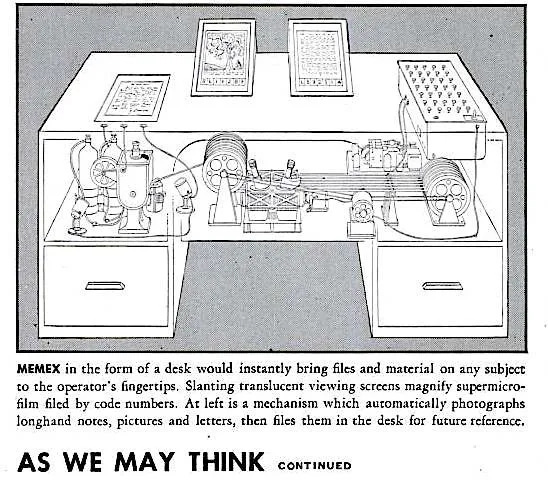

Between 1952-1956, a team of engineers at IBM built the IBM 305 RAMAC — the ancestor of every hard drive, server, or cloud. It was revolutionary for enabling instant access to data stored. Before the RAMAC, accessing data required feeding stacks of punch cards through machines.

For digital storage, this is the Trinity Test Site, the explosive center from which all else follows. RAMAC’s massive aluminum disks were coated in iron oxide, with little magnetic slots for data, bits to be read as they spun.

— Maxwell Neely-Cohen, Century Scale Storage

But the RAMAC’s reign was short-lived. Within just six years of its release, it was rendered obsolete in favor of something cheaper, faster, and denser. The focus in hard drive design swiftly pivoted from long-term reliability to speed, density, and size.

What most don’t realize, is that we’ve been capable of building data storage that lasts since the 1950s: “the RAMAC data is thermodynamically stable for longer than the expected lifetime of the universe,” said Joe Feng, one of the engineers who worked on the restoration. In a 2014 restoration project, researchers found readable data present on the RAMAC. Turns out, we got it right on the first try. We can build storage systems that lasts well beyond our lifetime. We’ve just chosen not to use it.

Cloud storage is more fragile than you think

Sure, millions go into protecting Google and Amazon’s data centers. But as Maxwell Neely-Cohen’s research at the Harvard Library Innovation Lab outlines, “the physical threats to data centers are not dissimilar to the threats faced by traditional libraries, with a few additions: fire, water, physical destruction…” The pivot from local to cloud storage has centralized global data, making it vulnerable in a different way. Let’s not forget the 2024 Crowdstrike bug.

Your data is safe insofar as it is in the company’s interests to keep it safe. All your files are maintained only IF Google chooses to maintain it. If Google had to choose between your data or that of a Fortune 500 company, who do you think they’ll choose?

The promise of abundant access

We tend to hoard: screenshots, digital receipts, photos of labels… we even send ourselves content we think we want to revisit (we never do). Why?

Maybe it’s because digital storage has gone from costing roughly $300,000+ per GB in 1980 to about $0.01 per GB today. Our storage capacity has increased exponentially. There is no pressing need for us to clean and organize our digital lives.

In 1947, Vannevar Bush, a leading American science administrator during World War II, wrote a famous essay titled As We May Think in The Atlantic introducing the concept of a “memex” (short for memory expansion) — a device that stores an individual’s “books, records, and communications, [that can be] mechanized so that it may be consulted with exceeding speed and flexibility.” He believed that a memex would maximize our access to memory and therefore knowledge, that increasing your capacity to store information also made you generally smarter.

While no official memex was ever built in Bush’s lifetime, the concept lived on. It even inspired one of the pioneers of the personal computer, Gordon Bell. Today, AI has taken (what I believe to be) the final form of a memex: put everything into a big drive, AI helps locate what you need. Not only do we have an abundance of memory, we also now have limitless access. But does it necessarily make us smarter?

Categorizing my life

The most grueling part of this experiment was cleaning up my digital life.

How does one even begin? Will that screenshot of that one hilarious text chain really be important in five years? Obviously. I found the hoarders subreddit helpful.

Up until now, I’ve approached digital housekeeping as an ad hoc task. Everything I store locally roughly falls into the categories of Screenshots, Pictures, Important Documents, Freelance Paperwork, and Writing. Not the most inventive names, I admit, but they do a decent job. Then came the challenge of everything I have online:

My Are.na links

“Favourites” lists

Instagram saves

Emails

Old Facebook photos (that I’m tagged in)

This entire newsletter…

I saved as many local copies as I could over the course of two weeks — I fashioned a phonebook1 of URLs, saved PDFs of emails… aware that I’m only saving the current versions of these internet artifacts.

LABEL THINGS PROPERLY

‘Accurately’ classifying information is a grave technical challenge. Jian Yang from Silicon Valley could attest to this fact. The premise of creating a system to organize my digital life intuitive to me was daunting— I misplace my physical belongings all the time, how will my digital life be different?

The process of figuring out how to sort everything I had saved sent me down a fabulous hole about the five laws of library science:2

Books are for use (will you use this file in the future?)

Every person has his or her book (organize by how you look for things)

Every book has its reader (names should be legible to others)

Save the time of the reader (simplicity is key)

A library is a growing organism (how you organize may change over time)

S. R. Ranganathan3 led the development of the world’s first major faceted classification system… I wonder what he’d have to say about the state of search today.

Invisible costs

Why carry all your memory around?

Just because you don’t feel it, doesn’t mean it’s not there. I don’t think I should be spending 200 grams of CO₂ — the equivalent of powering an LED bulb for ~50 hours — to store a photo I’ll never return to. I should bear the weight of my climate output.

I was inspired by former artist Emma Sulkowicz, who carried a 50-pound mattress around campus in protest of Columbia University’s refusal to expel a classmate whom she accused of raping her. The performance piece, Mattress Performance (Carry That Weight), gives the emotional weight of Sulkowicz’s experience a tangible form. It was a “pure radical vulnerability,” according to legendary art critic Jerry Saltz.

My digital memory is obviously different from (and much less severe than) Sulkowicz’s emotional struggle, but I felt that the same sentiment of giving a body to something shapeless was important. Unbeknownst to most, cloud computing makes up 5% of global greenhouse gas emissions. If I physically felt the full weight of my digital carbon footprint, would I still be hoarding as much as I currently do?

The average person stores 500GB of information in the cloud. The average weight of an 8GB thumb drive is 1 oz. This makes the average weight of a person’s cloud storage 1.76 kg. My belt (with all its bells and whistles) weighed a whopping 4.5 kg.

Archiving as an aesthetic

Now, why a skirt?

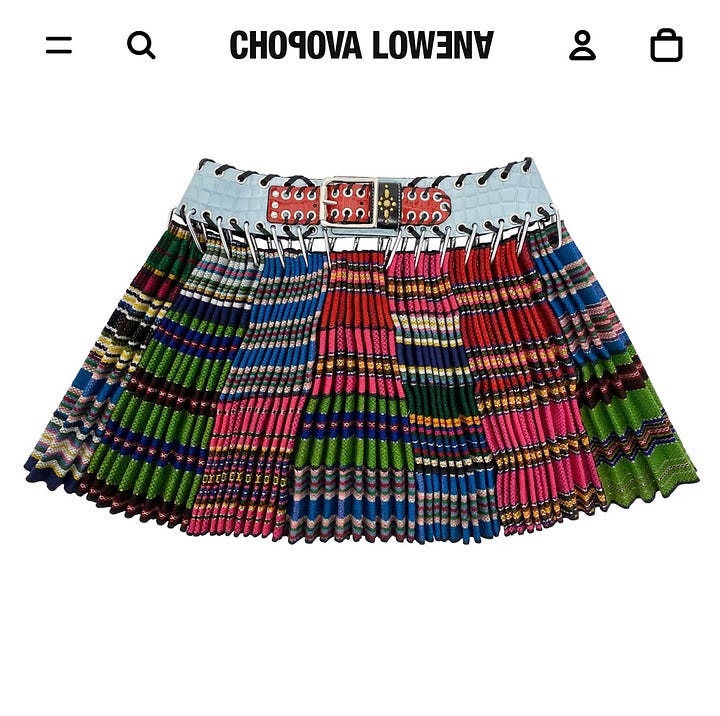

Years ago, I profiled the cult-fav British fashion brand Chopova Lowena for Vogue. How they spoke about sustainability really resonated with me — pulling up-cycled fabrics to craft visions of folklore… the idea of repurposing waste inspired me.

There’s also the fact that their pieces are a little more than what I can afford… DIY-ing something in the font of their ethos felt most attainable. Wearing the skirt around town did turn some heads, but thankfully I live in New York (so folks are used to it).

We’re seeing a resurgence of physical media. A rising trend of putting together “analog shoeboxes” of tangible memories (photo booth strips, ticket stubs, journals) is dominating the algorithm. And while the nostalgia-maxxing trend probably won’t last forever, this spirit of breathing new life into a forgotten form (USBs) feels significant.

**** Before anyone leaves a troll comment about how it’s impossible to fit my entire life into 20 USB drives, I’ll assure you that the rest of the memory lived in a pouch that I carried.

Of course, there’s a practical approach to doing this

The point of all this isn’t to evangelize the use of decade-old USBs.

There are more sensible ways of protecting and reclaiming your digital life. Archivists Alexis Durante-Tierney and Helen Vogelsong-Donahue’s article on archiving your digital life is a wonderful start:

We should be aware of the fragility of our digital presence! We’re putting too much trust in the system! It’s about time we took charge of our own digital possessions.

Hello! If you’ve made it this far — thank you for joining me on my neo-Luddite pilgrimage. If you’d like to support some of my more rogue ventures in cyber celibacy (typewriters, building a printing press… more to come), upgrade to paid! You’ll find treats sprinkled in your inbox <3

Kristoffer’s internet phone book helped inspire this approach

More on this in an upcoming post!

S. R. Ranganathan is the father of information and library sciences.

I've been thinking about this recently. Specially about how can I be sure that the important bits don't disappear. But first I have to do the curating part. Not everything is worth archiving.

Thank you for a tangible recipe on how to reclaim my digital life! I've been meaning to get around to this but never do... and my friends talk about this stuff often! I studied comms and tech so this stuff is my Roman empire lol