I quit texting for snail mail

The end of Denmark’s post office and the utopia of bureaucracy

In 10 days, Denmark will stop delivering letters. The Nordic nation’s postal service PostNord is set to take down roughly 1,500 mailboxes in the coming year, but package delivery service will remain. Apparently the number of letters mailed in Denmark has decreased by 90% since 2000. Shocker!

Cancelling snail mail seems a little definitive. Sure, I’ve gotten my rent cheques stolen and my application forms lost, but courier services have been around since 2000 BC. Nothing quite beats the warmth of receiving a handwritten letter.

I was reading David Graeber’s Utopia of Rules when I learned that in the late nineteenth century, the German postal service was considered one of the great wonders of the modern world… and somehow inspired the organization of the Soviet Union? More on this in a second.

To commemorate the 400-some years of the Danish post office, I decided to give up texting and, instead, write letters.

I wouldn’t be the first to think of doing this. My friend Skyli recently wrote a piece for Teen Vogue about how Gen-Z is turning to the slower pace of handwritten mail. I even got a couple pen pal requests in my (digital) inbox.

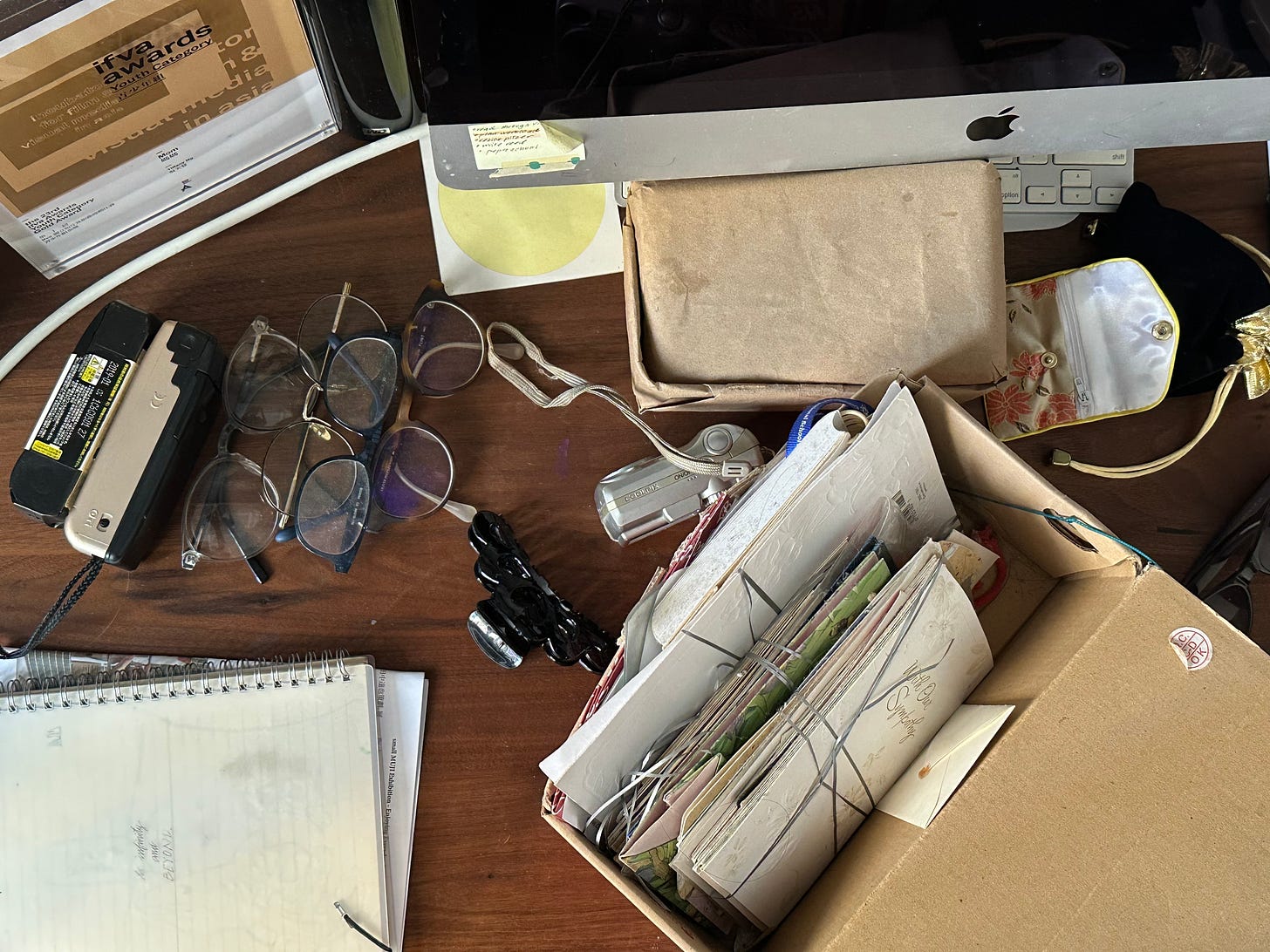

To clarify, I couldn’t stop texting everyone: I wrote to my long distance friends. Having grown up in Hong Kong, many of my closest friends are sprinkled across the globe. We kept in touch mostly through texts and sporadic facetimes, but now we correspond through letters.

What I gave up: texting

How did I cope: mailing handwritten letters

Did it suck: not at all

Texts are ephemeral, letters are forever

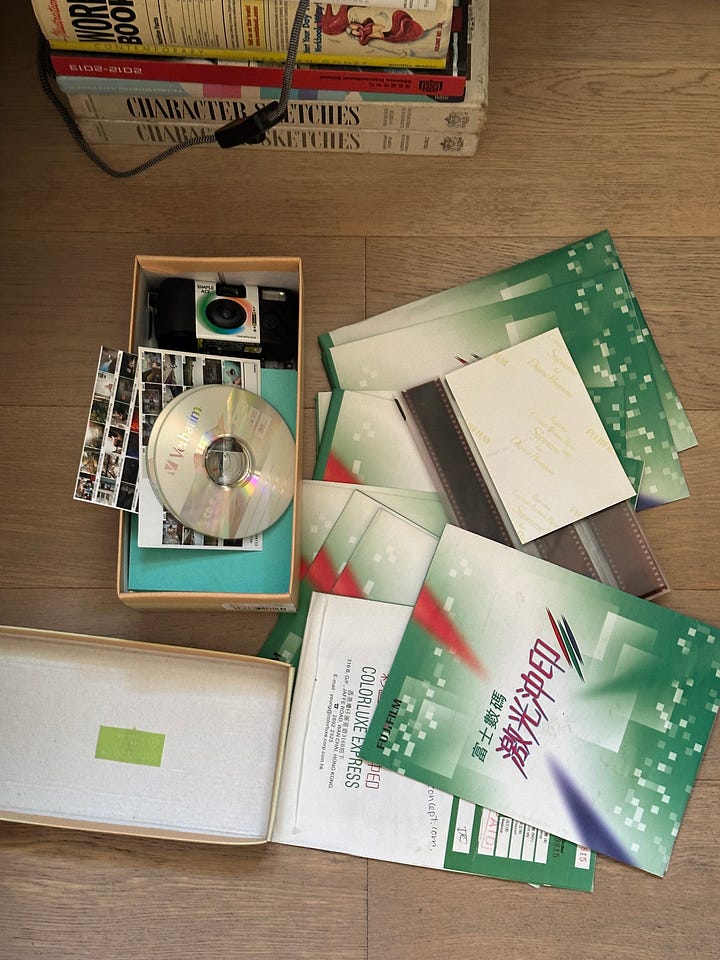

My most cherished possessions live in shoeboxes stacked high in my childhood bedroom: letters from (and to) secret admirers, notes from ex-boyfriends… I once received a comic book someone (a crush) had drawn about us. When my childhood best friend moved to Thailand, we wrote each other barely legible (but adorable) letters. When I graduated high school, my friend Kwok and I went on a trip to Taiwan, where we wrote each other letters to be mailed a full year later. My friend Divy makes these gorgeous holiday cards that I look forward to collecting every year.

But as I grew up, I started filling up less shoe boxes.

Max Neely-Cohen did this gorgeous study on century-scale storage for the Harvard Library Innovation Lab, where he asserts: “even today, if our goal is storing information for a century, we should not underrate the power of print.” Contrary to the idea that digital is forever, Max’s study outlines the fragility of hardware and cloud storage — Tech Review’s Niall Firth concurs.

If all my memories live on the cloud, what happens if Google’s data centers go down? Or if I decide I can’t keep paying a monthly subscription? The number of times I’ve been able to locate and re-read an old letter proves just how the humble shoebox stands the test of time. When was the last time you re-read a text chain?

If it isn’t broken, let’s not fix it.

Decontextualization and streams of consciousness

When I sat down to write my first letter, I was overwhelmed.

Where I do begin? What do I include? With my limited space, I had to prioritize some thoughts over others, but there wasn’t an explicit purpose to my letters — I wasn’t asking for something, nor was I trying to get something out of it (unlike my many, many pitch emails). There was no clear start or finish, no default hierarchy.

When my texts are either one-off thoughts, sporadic updates, and links to funny things I encountered on the internet that day, I was stumped when formatting a letter. My texts are devoid of context — how do I weave the fragments of my life together?

The timeliness of texting in contrast to the formality of letters makes sharing the very minor inconveniences I experienced that day seem silly. I had to remind myself: salon letters of 17-18th century France often served this function. Eugenia MUST know how I stubbed my toe, even if it’s 2 weeks after the fact.

I learned, from the fab Kristoffer, that mail was delivered 12 times a day in Victorian London. If there was a limit to how much we could text (like there was in the early 2000s), would we only share more coherent, substantive thoughts? I admire people who text once a day — Jonathan Groff-style.

It was relieving, being less in the know

The thing about snail mail is that you don’t know when something has been delivered. It’s also been so long since mail was the primary form of correspondence that there’s no clear etiquette on how quickly you need to respond. No read receipts either.

Where I’d expect a text back within a couple hours, days or weeks are fair game for letters. The lack of pressure to respond felt freeing: I could take my time. I wasn’t reading into why I was getting ghosted. My letter could’ve gotten lost in transit.

How the post office created the internet

When I found a carrier pigeon service in Texas a couple months back, I went down a rabbit hole and learned that the German post office in the 19th century was one of the first attempts to apply top-down, military forms of organization to public good.

As we find ways to retreat to analog in protest of Big Tech, it’s important we also understand the context of these seemingly archaic forms of communication.

David Graeber in Utopia of Rules draws a parallel between the history of the German post office and the formation of the (American, I guess) internet:

A new communications technology develops out of the military.

It spreads rapidly, radically reshaping everyday life.

It develops a reputation for dazzling efficiency.

Since it operates on non-market principles, it is quickly seized on by radicals as the first stirrings of a future, non- capitalist economic system already developing within the shell of the old.

Despite this, it quickly becomes the medium, too, for government surveillance and the dissemination of endless new forms of advertising and unwanted paperwork.

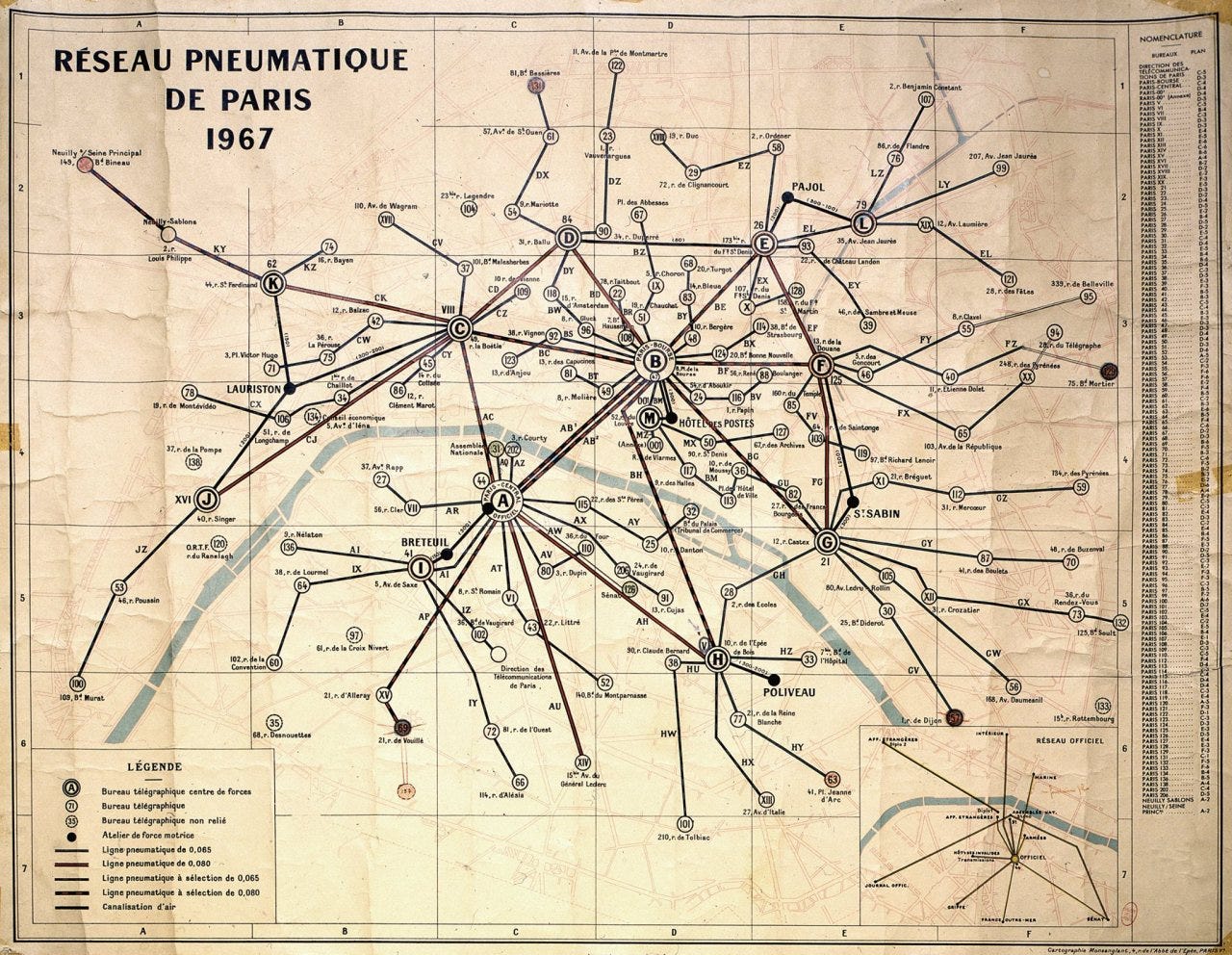

Graeber talks about bureaucracy as a form of poetic technology, where mechanical forms of organization (pneumatic tubes) can realize impossible visions.1 But like in Spiderman: with great power comes great responsibility.

Postal services were built for armies or empires. It was the public’s adoption of this system that gave those in power a new form of social influence. Funny isn’t it, that we renounce modern tech because previous iterations are just the lesser of two evils?

We’ve come full circle.

Letters help me slow down and collect my thoughts, but I did miss the joy of sending and receiving texts out of context. Should all correspondence be coherent? Or is there something to funny, albeit ephemeral, memes?

This holiday season, write your loved ones a letter. See where your handwriting takes you. Give something your recipient can hold onto (literally) for decades.

****

Hello! If you’ve made it this far — thank you for joining me on my neo-luddite pilgrimage. If you’d like to support some of my more rogue ventures in cyber celibacy (typewriters, building a printing press… more to come), upgrade to paid! You’ll find treats sprinkled in your inbox <3

He then dives into an interesting (but less relevant) philosophical self-monologue about Hume and Aristotle’s conceptions of rationality.

Amy Dacyczyn, author of The Tightwad Gazette, made the following suggestion in the late 80s and early 90s to save money:

Instead of expensive long distance calls to family members, one could send a three page letter for the cost of a single US first class stamp (25 cents).

I've been Groff texting for a few months and it's made me less glued to my phone. Now hoping to send more notes out!