Maybe we should be skeptical of the Aussie social media ban

Bans won’t bring back pre-smartphone era bliss. We need more.

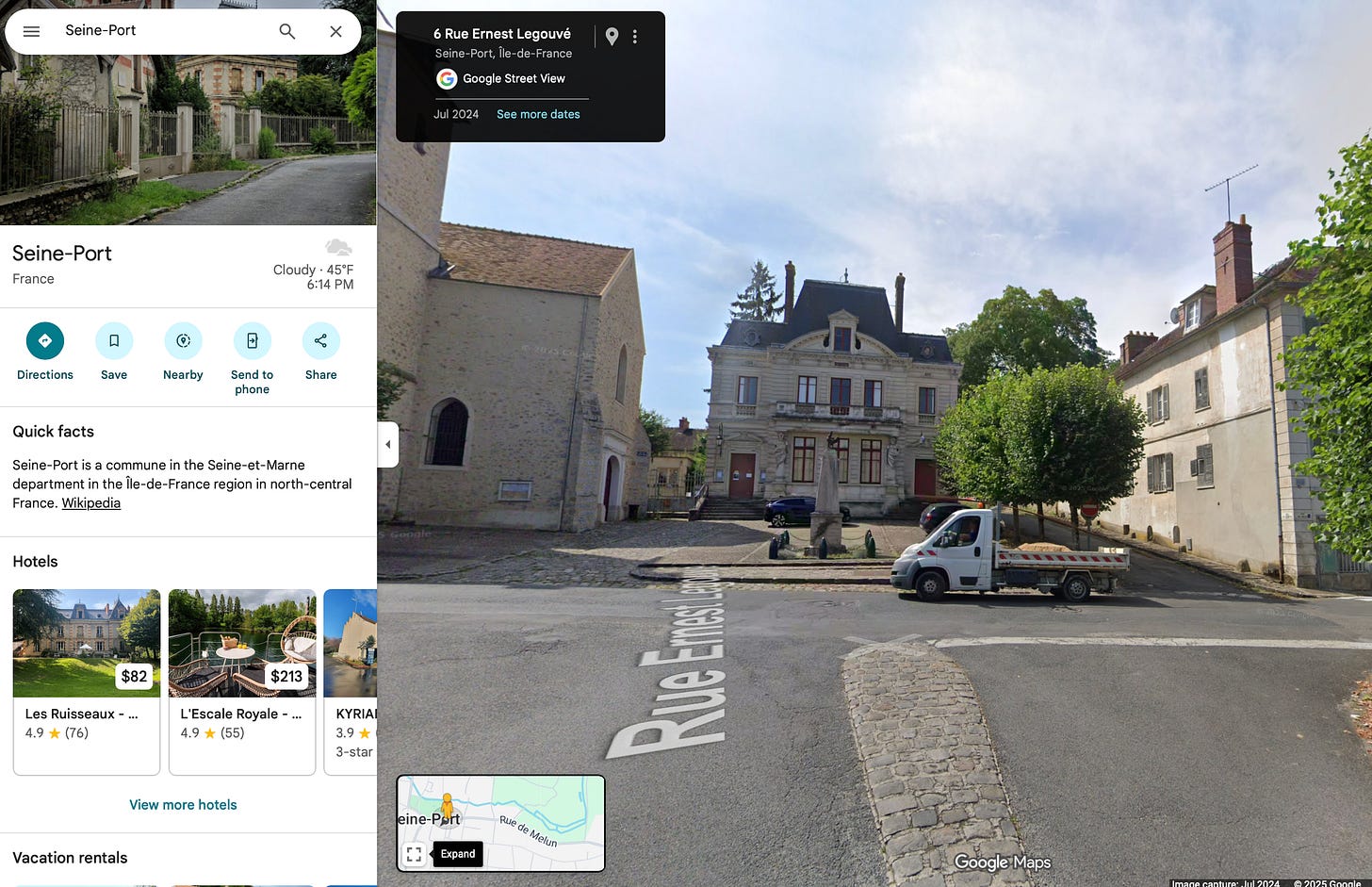

While the tech detox conversation has taken many forms in the US, it’s difficult to imagine a reality where the anti-tech movement takes any legislative shape (the US is home to Silicon Valley after all). But elsewhere, the tech resistance is finding its place in policy. Australia’s age-based social media ban went into effect this past week. In Seine-Port, France, scrolling in public is illegal. In Ulko-Tammio Island, Finland, you’re given a sticker to cover your screen to properly engage with nature.

Are they working? Should the US follow suit?

My sense is — we should be taking these policy proposals with a grain of salt.

Reverting decades of brainrot is not as simple as a blanket ban. After all, internet blackouts have long been deemed a human right violation by the UN.

Hear me out.

Don’t get me wrong, social media IS ruining adolescence

At the very least, spending more than 2 hours a day on a smartphone leads to sleep deprivation — according to Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. America’s surgeon general declared “war on social media” in 2024 and put out an advisory on social media’s impact on youth mental health, warning that “we cannot conclude that social media is sufficiently safe for children and adolescents.”

I don’t need to explain why screen time is detrimental to our mental and physical health. You get it.

BUT studies conducted on teens subject to social media bans around the world have been inconclusive, one even suggested that blanket bans have “no significant difference in academic grades or wellbeing between schools with strict phone bans and those with more relaxed policies.” Why?1

This reaction to such ‘revolutionary’ bans boil down to a few reasons:

Kids will always find a way. There’s the one universal truth about teenagers: banning something only makes it more enticing. Workarounds are abundant.

Technology is embedded in modern education. Relationships are strained when teachers are free to use technology to teach but students are barred from using technology to learn. (In Aotearoa, New Zealand, where a smart phone ban has been active for over a year, 80% of students say technology in class is distracting – not just phones. So, what’s the point?)

Students aren’t given practical alternatives. I’ve long preached that quitting cold turkey doesn’t work. There will always be conniving alternatives. Would reframing our relationship with tech be better?

The slippery slope

When I was working with the Yale Humanitarian Research Lab researching the role of social media platforms in facilitating mass atrocities, I spent much of my time making the case that, in our current moment of connectivity, ANY nation-wide influence on internet access should be subject to heavy scrutiny (read my full research on Vox).

Internet access evolved from being a luxury to now being a core part of societal infrastructure. It is how people access critical information, pay their bills, find community, and stay informed — TikTok is currently the go-to news source for 63% of Gen-Z. Ceasing social media or smartphone access would force people to pivot, but I’m concerned that these bans could be a slippery slope.

Sure, bans today are almost exclusively targeting children and screen time/social media. But what’s stopping regulators from going further? To raise age limits and expand the coverage of what’s banned? When our media culture has accepted access to the internet as the status quo, how should we expect people to adapt? Who gets to decide what “limiting access” means?

Just a few years back, any restriction of internet access would be immediately ruled as censorship. The United Nations has published reports on how “the dramatic real-life effects of Internet shutdowns on people’s lives and human rights have been vastly underestimated.” Who’s to say a social media ban doesn’t spiral into an internet ban?

But the blackout also means killing the algorithm!

You’re entirely correct. When speech is regularly siloed, shadowbanned, and selectively (algorithmically) amplified, is a black out really so bad?

The internet was once seen as a free marketplace of ideas. It is now a series of iron-clad echo chambers. Cutting social media access theoretically tears down these bulletproof walls, but it also risks taking out the platform entirely.

We need a way around the algorithm. Our epistemic architecture is not equipped for the complete removal of social media or smartphones because how we retrieve and synthesize information has changed too much. For one, people ‘ask’ for answers rather than ‘surf’ for information now.

In the case of education/intellectual enrichment, Jay Caspian Kang’s New Yorker column this week insists that we need to change how we think about literacy. He asks: will we read more books if we quit social media? To answer this question, Kang spoke to star Substack-er Celine Nguyen (icon) about how, despite reading fewer books, the internet helps her read smarter. She said: “That is something special about the internet: That you do not need to be in the right social context where these things are automatically accessible to you.”

Kang and Nguyen may be specifically speaking to our shifting relationship with reading but they nonetheless gesture towards a shift in our status quo. How we find and consume information has fundamentally changed since a pre-internet age.

In the absence of screens, socio-economic backgrounds become relevant.

In a 2025 census about Media Use by Kids Zero to Eight, it was found that children from lower-income households are spending nearly twice as much time with screens as those from higher-income households. The same survey noted that parents of higher levels of income were more likely to spend time reading and engaging with their children — something lower income households couldn’t afford (many parents reported having no time or being too burnt out).

In a world where social media is often used as a search engine (74% of Gen Z users rely on TikTok for search), what could banning social media mean? What would limiting screen time —as Japan has done— do to a child’s ability to easily explore new hobbies/interests? Where higher income households may be able to provide fun alternatives (tutors and classes), could a ban also limit critical access to information and avenues of exploration for lower-income demographics?

Going back isn’t as easy as pulling the plug!!!!

To be crystal clear, I’m NOT advocating AGAINST these bans. Only time will tell how effective they are, but I wonder if there’s something to be said about fostering more constructive2 relationships with technology rather than banning it entirely. For example: how can we bring back AI-less3 web search?

The efficacy of internet bans depends on the infrastructure we build to replace it.

This week’s essay started as a survey of anti-social media policies that have been implemented around the world (before my caffeine-fueled jitters pushed me down a darker rabbit hole). And while I’m not privy to an internet alternative that solves everything I mentioned above, I did find several softer approaches that I found fun:

The French Revolution

If “visual pollution” can be a legitimate reason against wind turbines, we can ban scrolling in public for being an eyesore. “I want to preserve public spaces from the smartphone invasion,” said Vincent Paul-Petit, centre-right Les Républicains party mayor of a small village south of Paris (he’s seeking re-election… it’s not looking good).

I should be clear that the scrolling-ban is not legally enforced. Local businesses and public spaces are merely encouraged to put up signs that discourage screentime. The village also offers teenagers dumb phones in lieu of a smartphone — similar to a program in Chile where schools are piloting programs that block cellphone signals.

Seine-port residents seemed to disagree with Vincent Paul-petit, despite voting in support of the ban (you cannot make this up). The village has a population of ~1900 residents, of which 150 voted in support of the initative (only 20% of the village voted):

In France, 57% of people aged 18-39 showed signs of addiction and 67% of French adults exhibited compulsive smartphone use.

The Finnish Resistance

Finland’s Ulko-Tammio island is apparently “The World’s First Phone-Free tourist area.” In 2023, Parks & Wildlife Finland announced that tourists visiting the island will be given stickers to cover their screens. There’s phone service on the island if you need it and detoxing isn’t mandatory, but the general sense is that you’d be going against the grain if someone sees you glued to your phone. Oh! You also need to take a boat to get to the island.

Many called this initiative a marketing ploy. Others celebrated the statement it made. To me, it seemed fixing a gaping water leak with sh*tty tape. We have the option to be phone-free at any given time of day, anywhere in the world. Must you travel to detox?

On the note of basic human necessities, there was a time when Free WiFi was an ammenity. Now, the absence of cell service is an asset. It’s marketed all over AirBnB. Rebranding signal blackspots as ‘wifi-free retreats’ is hilarious (but smart) to me.

Is it that hard to conjure the willpower to put down our phones? I think yes. I mean, this whole blog is about finding new ways to trick myself into being online less. Chaining a phone to a wall, retreating to the forrest… Finnish reddit seems to agree.

Honorable mentions

(The NYTimes wrote a survey here, too)

Toyoake, a municipality in Aichi Prefecture, Japan passed a bill proposing limiting smartphone usage to 2 hours a day.

The Chilean Senate’s education committee endorsed a bill this past August that prohibits and regulates digital device access in schools across the country.

New Zealand’s 2024 smartphone ban in schools has yielded mixed results.

The generation that social media bans target is also the one leading the anti-tech charge

Since starting Cyber Celibate, I’ve gotten to know several many anti-tech evangelists. Most of whom, I’m slowly discovering, are either my age or much younger!

Being the ones born into social media and screens, perhaps we’re the ones best equipped to lay out the path forward; To find a way around the algorithm.

I do think social media age limits are critical in preserving the sanctity of our youth, but that shouldn’t be where our fight against screentime ends. At the end of the day, if the change doesn’t come from within, will it really stick?

I’ve been preaching a slow weening off rather than quitting cold turkey. But do you think the solution is a ban? Let me know what you think!

Hello! If you’ve made it this far — thank you for joining me on my neo-luddite pilgrimage. If you’d like to support some of my more rogue ventures in cyber celibacy (typewriters, building a printing press… more to come), upgrade to paid! You’ll find treats sprinkled in your inbox <3

I was going to say intentional, but NYT’s Marie Solis outlines why I shouldn’t here.

ChatGPT’s group chat function seems to be attempting to make the LLM social…

This was so interesting! Bans like these worry me, we treat children like lab rats and less-than-people, the internet did a lot of bad things for me as a teen, but it also taught me sex education, critical race theory and that being gay was okay in my conservative-leaning community.

Your point about infrastructure is such a good one too! I research histories of adolescence and teens of the past had letter-writing, magazines, radio, third spaces like cinemas and places to loiter, teens are left without any of these organic resources and then, suddenly, no phones either!

mild tangent: in the mid00s to mid10s, i used to frequent this website for kids that revolved around flash games but had plenty social and creative aspects too, it was quite popular at the time in my country (estonia; mängukoobas the site was called), but it was left dying a slow founder-disinterest death as social media started slowly taking over online, before being closed for good in 2021.

and really a part of me still mourns the fact there don't really seem to be any known suchsort sites for kids and youth these days, with social media seeming to be the primary choice for them these days.... any actually productive systematic solution against that would likely take a lot of effort, i feel like.