Physical media: why we just want to feel something

Imogen Heap's MiMu gloves, touch as a product feature in tech, and why tangibility is a luxury today

Late stage capitalism has made touch a product feature (screen protectors that feel like paper, keyboards that click like typewriters) — but could Imogen Heap’s haptic gloves make this a good thing?

All we really want is to feel something — the reassurance of earphones being properly plugged in; the security of a seatbelt clicking into place; the crisp fizzle of a soda can being opened. But today, everything is digitized. Our lives feel weightless. We crave physicality as Big Tech full sends VR. We’ve lost any sense of stability.

We forget that a website can actually weigh something. As Byung-chul Han argues in his book Non-Things, our society has shifted from tangible objects to marketable information, where decontextualization and the lack of resistance cultivates an ever-growing sense of precariousness.

(I realize I quote Han way too much, but he literally wrote a whole book about this)

“The earthly order, the planetary order, is made up of things that take on a lasting form and create a stable, habitable environment… Today the earthly order is replaced by the digital order. The digital order derealises the world by making it computerized.” — Byung-chul Han, Non-things.

According to Han, digitization enables disassociation — the intimacy of wearing in our tech is rendered obsolete.

We used to have more tactile relationships with our tech

Remember how we’d train ourselves to type differently when our ‘E’ keys gave out?

There are simply less buttons to press today.

When Apple ended Blackberry’s reign with an announcement of the iPhone on January 9, 2007, then-CEO Steve Jobs made history by dragging Blackberry’s signature design: “they all have these keyboards that are there whether or you you need them,” he said, “but every application wants a slightly different user interface.”

Jobs insisted that the iPhone was revolutionary because it consolidated the functions of all our seemingly-indispensable single-purpose devices. With the iPhone, everything can be an app, all because there’s a big screen that is infinitely adaptable.

We’ve normalized reading the news, doing math, ordering food on the same device. We enter and exit ephemeral interfaces that change with each software update. Nothing feels real because we’re literally not feeling anything. According to a study done by the University of Illinois that involved isolating monkeys through pieces of glass, a lack of touch causes brain damage!!

CDs, magazines, books are all things we can touch. Maybe that’s why they’re making a comeback. Creators are going viral for showing off their zine/magazine galleries and CD collections. Record stores, though mostly also cafés, are popping up everywhere. I recently got trampled at the Printed Matter NY Art Book Fair (in the famously-musky zine tent), so this must be a trend.

Ah, the romance of physical media

The return of #physicalmedia may be motivated by nostalgia, but it also speaks to something deeper, more primal we crave — touch. Like ghosts, we need to see (feel) it to believe it. *Cue Derek Thompson’s spiel on America’s loneliness epidemic*

I don’t think I’m alone when I insist on paperbacks over a Kindle. The weight of creased paper gives me a sense of accomplishment that keeps me reading.

This may be a bit of a stretch but bear with me: to touch is also to be seen. To touch is to ground yourself, to reaffirm your existence. An accidental dog ear, stains from sips of tea, shreds from pages torn out of a notebook all gesture towards some form of human presence. Past or present.

“Touch , by clarifying and adding to the shorthand of the eyes, teaches us that we live in a three-dimensional world.” — Diane Ackerman, A Natural History Of The Senses

Today, all our digital experiences are all shiny and clean, void of stains and imperfections. You can refresh a page to your heart’s desire. Nothing can bleed outside the margins. Traces of engagement are quantified in Likes, Views, Comments — all numbers that are inevitably inflated to nudge you towards a career in content creation. Everything kind of looks the same.

The key difference between trails online vs. in real life is the implicit perception that comes with engaging with anything online. We’re not free to be unhinged online.

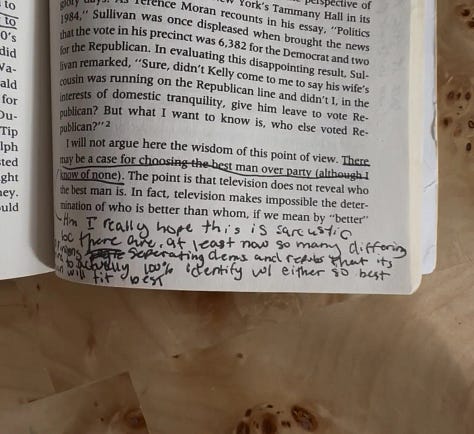

Got this book secondhand. The original owner really disagreed with the author. What a treat.

Books are a great example: I may enjoy a paperback more than a Kindle, but a used (preferably annotated) paperback trumps all. It’s like reading with a friend and getting a cheat sheet to the material, half-blood prince style. The best part? Each annotation is not driven by its potential to signal intellect.

The very personal nature of owning printed material presumes a degree of privacy. To read these annotations one has to physically hold this book in hand. Copies can’t easily be made, nor can notes easily be shared.

Touch has become a product feature

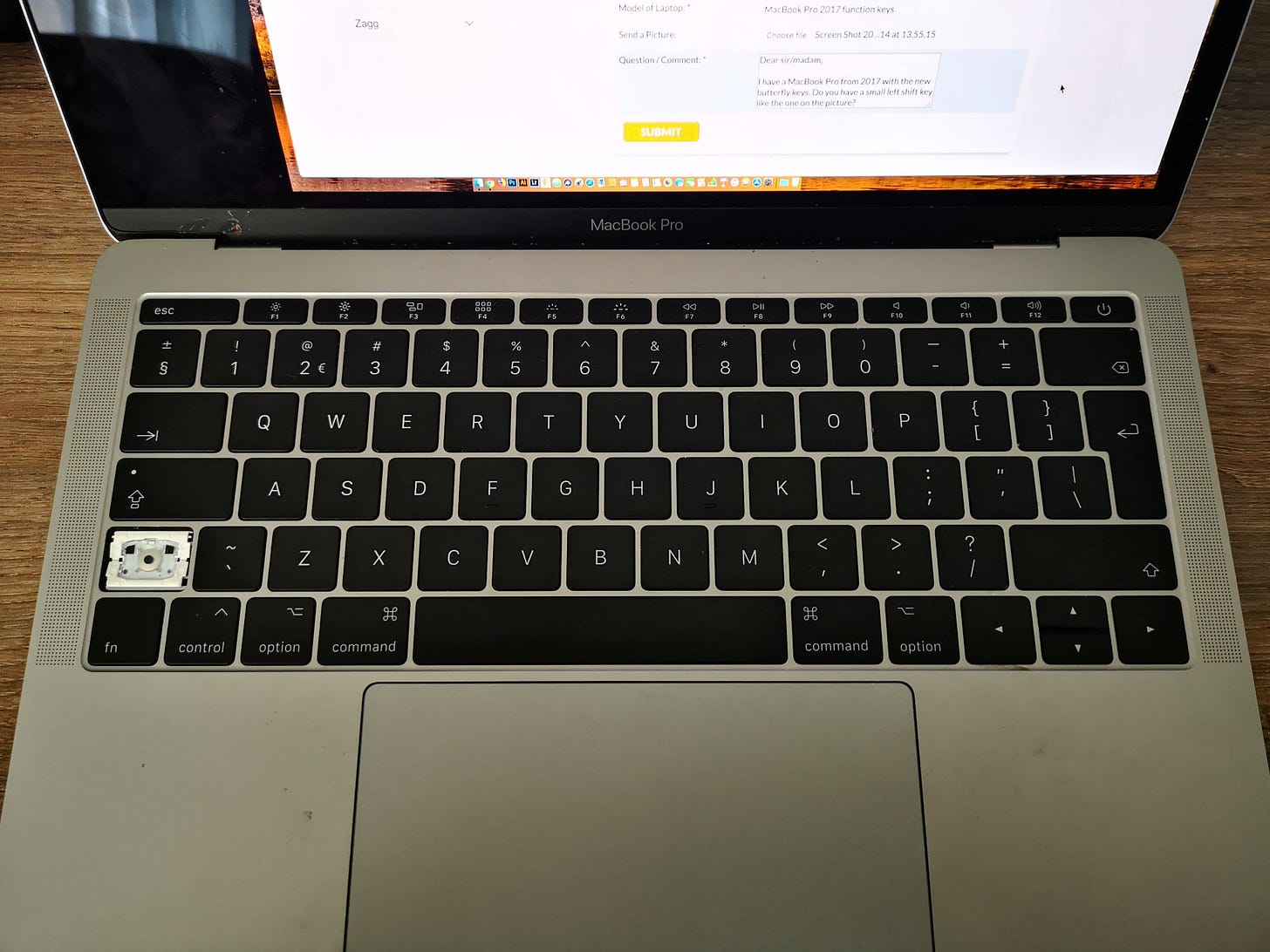

Don’t get me wrong — touch is still important in tech, it’s just marketed as a premium feature. iPad screen protectors that feel like paper, mechanical keyboards, capacitative touch screens (I don’t really know what this is either)…

I should clarify that there are innovative ways that people are reimagining the role of touch in tech. For one, Philadelphia company Music: Not Impossible reappropriates the haptic technology used for VR gameplay to facilitate full-body listening. That’s right — the suits people wear to simulate bullet impact in Call Of Duty are now being used to help hearing impaired people experience music.

By creating ankle bands, wrist bands, and a backpack that’s programmed to vibrate specific registers of a song, Music: Not Impossible adds a new dimension to the experience of music. They’re currently exploring adapting this tech to capture other sonic experiences (eg. dogs barking, crack of a baseball bat), integrating touch in a way that isn’t excessive or redundant.

We still have strong feelings about how our tech feels. The vehement, almost nation-wide revolt against Apple’s heinous 2015 butterfly keyboard can serve as a reminder.

Tech that leverages physicality

Steve Jobs thought that the personal computer would be the bike for the mind, so much so he almost named the Macintosh the Bicycle. He’s right, sort of.

Apple, often credited for introducing the concept of user experience, pioneered the idea of adapting tech to each user’s habits. Where people were expected to learn how to use technology in the past, Apple insisted the future was the other way around.

But lately, it seems that UI conventions are starting to influence our mannerisms. We’re subconsciously conforming to constraints in tech: phantom pings, TikTok speak… with the popularization (and increasing demand) for prompt engineers, we’re literally learning how to communicate with the technology we’ve built.

Imogen Heap, English musician/technologist/personal idol of mine, brings back Jobs’ original promise of human-first usability with MiMu gloves — wearable synthesizers that Heap developed herself.

“I wanted to be able to reach into the software in my laptop without having to stare at it,” Heap said as she waved her hand to create an audio loop in a demo with FKA Twigs.

By encoding Ableton commands into physical gestures, Heap captures the instinctual character of music production. She eliminates the need to translate a sonic sensation into a button, making the tech work to understand her (and not vice versa).

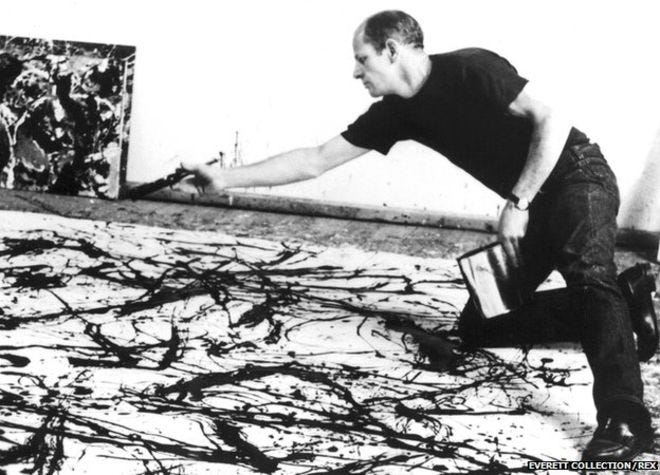

Jackson Pollock, known for his expressive paint splatters, was an early adapter of expressive and instinctual creation. Considered the father of Action Art, Pollock’s paintings were mere records of his gestures of aggression, traces of his expression, not so much a composition. His body was the brush and the cans of paint were his ink. He didn’t have to translate his emotions, his paintings spoke for itself.

In many ways, Heap’s gloves facilitate a sonic version of Pollock’s primitive expression. By factoring in touch in technology, Heap reinstates the importance of physicality in tech — to touch and be touched (by music).

At the very least, Heap gets us out of bed and upright. I could go on forever about Heap’s MiMu gloves. If you’d like a separate post about it, leave a comment below :)

Think about it, is an IG Like really better than a hug?

Touch, for all its ability to stabilize and ground us, can also be reimagined to enhance our everyday experiences (when used, of course, appropriately).

Where we’re retreating to physical media as an antidote to our burgeoning digital disassociation, technology like Heap’s gloves reminds us that movement, physicality, and presence can also be innovated for good. Maybe (to oversimplify my longer-than-usual rant this week), the solution to all this is a nice long huge and squeeze.

***

Hello friends! I recently enabled paid subscriptions to support some of my more rogue ventures in cyber celibacy (typewriters, building a printing press… more to come).

I also created a Snail Mail Membership, where (in true neo-luddite fashion) I’ll physically mail you this newsletter on a bi-monthly basis. For the first dozen snail mail members, I’ll handwrite your first letter <3

Imogen Heap’s tiny desk concert featuring the MiMu gloves changed me! There’s such a tenderness in the exchange between her/ableton/the gloves and the audience. I love how the gloves are an exploration of space and movement as much as they are of sound.

I totally agree with that idea. I'll just go buy myself a print newspaper and some old tech gadgets like an MP3 player or Walkman. I will replace digital with analog. ❤️