Who were the original anti-tech evangelists?

Luddites and how to become one.

It’s cool to hate on tech. It’s easy to fixate on the troubled 0.001% profiting off our free data (so much so we sometimes forget about the oil tycoons/gold trades/rare earth mineral dealers fueling wars). What’s difficult is understanding why we should hate on tech or, better yet, how to selectively resist it.

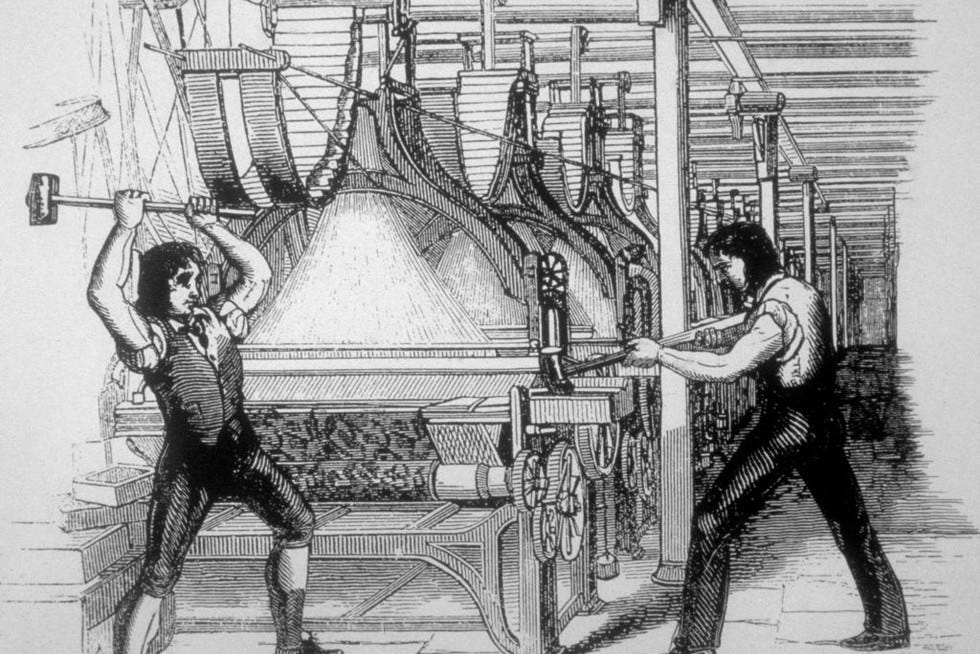

When the premise of rejecting technology comes up, many point to luddites — textile workers in 19th century Britain who protested the adoption of specific large scale technology. And while they made their names by breaking machines, they didn’t reject technology itself. It was the harm that technology posed on people that was central to their cause. They were selective about the machines they destroyed. They were technologists themselves.

I recently attended a conference about our renewed interest in Luddism in the age of AI. Professors flew in from around the world, tech workers affected by the AI-boom spoke about their experiences, and anti-tech activists laid out their framework of resistance. Here’s everything I learned —

Who were the luddites?

They were the first to act on the threat of unbridled technological advancement. When automated textile equipment started threatening the livelihoods of skilled workers, encouraging child labor, and enabling the degradation of working conditions, the original luddites selectively destroyed machines to put pressure on their employers and demand better working conditions.

They were creative technologists, craftspeople who spent their lives perfecting a skill that was being threatened by automation.

They selected machines that posed a specific socio-political threat. In many cases, they counted the frames on looms before breaking it (the number of frames were proportional to the amount of work the machine would replace).

Let’s not forget: looms were precursors to computers

The luddites were named after Ned Ludd, an apocryphal weaver who smashed two stocking frames in 1779 after being told to “square his frames.”1

The machines and the iron hammers used to break them were made by the same blacksmiths. Enoch was his name. I found his burial grounds here.

I spoke with Mat and Ana of Breaking The Gloom, a luddite chapter based in London. “The better you get at it the less you believe in the myth around it,” Matt said. Coming from a background in programming, they spoke about the ‘contradiction’ of being anti-tech online (…more on that soon).

***

Deskill to displace

Our growing dependence on technology limits our individual autonomy, and as our skills narrow, we become replaceable. Starbucks baristas no longer misspell our names on cups (we have printed order tags now)… Cursor writes code for most entry-level engineers… what capitalistic value do we have left? Management consulting?

Today’s highly reliable engines seal off their secrets. Slide rules yielded to calculators, calculators to computers. Each time, individual virtuosity waned, but overall performance advanced — Kwame Anthony Appiah, The Age of De-Skilling

According to Professor Appiah, the rise cognitive divisions of labor is creating specialists who inherit conceptual tools they can use but can no longer make. Our collective bargaining power as (tech bros endearingly call) cogs in the machine dwindles with every ChatGPT prompt. The solution, apparently, is more automation.

To be absolutely clear, it’s almost never the laborer’s choice to participate in the frivolous integration of technology in the workplace. They’re merely subject to it. Amazon’s push to automate half a million jobs markets what once was a meme: Fully Automated Luxury Communism (FALC). A post-work, post-scarcity society — Abundance-style. Of course, whether that vision carries the C in FALC is a different question.

For every step forward, we’re taking two steps back: the right to repair movement is making headway fights against proprietary technology, just as literacy rates plummet with the rise of AI. Even if hardware monopolies like Apple or Google give us free reign to tinker with their devices, chances are we won’t know how.

Even beyond the workplace, skills have also been commodified — every hobby needs to be a side hustle, every meal needs to be documented for content. Yet, we’re not actually pushing ourselves to learn. We’re buying paint-by-numbers kits because we don’t want to sit through the discomfort of butchering the Mona Lisa.

***

What is neo-luddism?

I’ve been hearing whispers of terms like New Luddism, neo-luddism, anti-tech lately. Some are advocating for flip phones and severing access to internet, others preach intentional relationships with technology. I feel like I’m somewhere in between.

To me, neo-luddism is understanding how your technology works, how you’re using it, and being critical of its affects on your life — beyond screen time, quitting cell phones and social media. When is it excessive? When is it actually helpful? I know, no one can make a pencil one their own. There’s no need to smash a computer.

Making things harder for yourself is a form of resistance. Your skills are what make you valuable. By limiting our dependence on technology, we protect ourselves from another subscription service and the looming threat of being replaced by machines.

Resistance and resources!!1!!1

There’s no straight answer for how we should fight back. Tech *celibacy* is often a luxury and “connectivity” has been woven into our social fabric. This is a reminder that things are meant to be difficult! When we outsource everything, what’s left?

Tech resistance is (digital) civil disobedience. We may not have to smash machines like the original luddites, but we can cut off access to our data, disable AI integrations, and fix old laptops. We can start small.

**** Trying out a new format this week for my lovely paid subs — at the end of my Sunday posts, I’ll occasionally include some relevant reading/rabbit holes I’ve loved this week in lieu of our usual weekly roundup :)

To go

Let’s quit Spotify together! Swap CDs/cassettes and learn about streaming alternatives — Dec 6th, 2-5PM at Boshi’s Place

To read

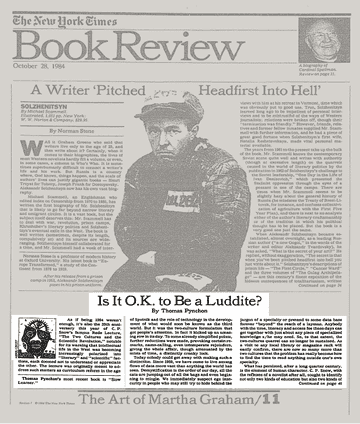

Is it O.K. to be a luddite? — Thomas Pynchon, 1984, NYTimes Archives

Sabotage — Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, 1917, IWW Publishing Bureau.

The Age of Deskilling — Prof. Kwame Anthony Appiah, 2025, The Atlantic

Fully Automated Luxury Communism — Aaron Bastani, 2018 + (heavily cited in Ezra Klein & Derek Thompson’s Abundance)

Blood in the Machine — Brian Merchant, 2023

Machine Breakers — Eric Hobsbawm, 1952, Past & Present

To view

Guillermo del Toro’s Frankenstein — Brian Merchant wrote a fabulous review of the film and its Luddism influences on his Substack, Blood in the Machine.

Abeba Birhane’s talk on algorithmic injustices and relational ethics

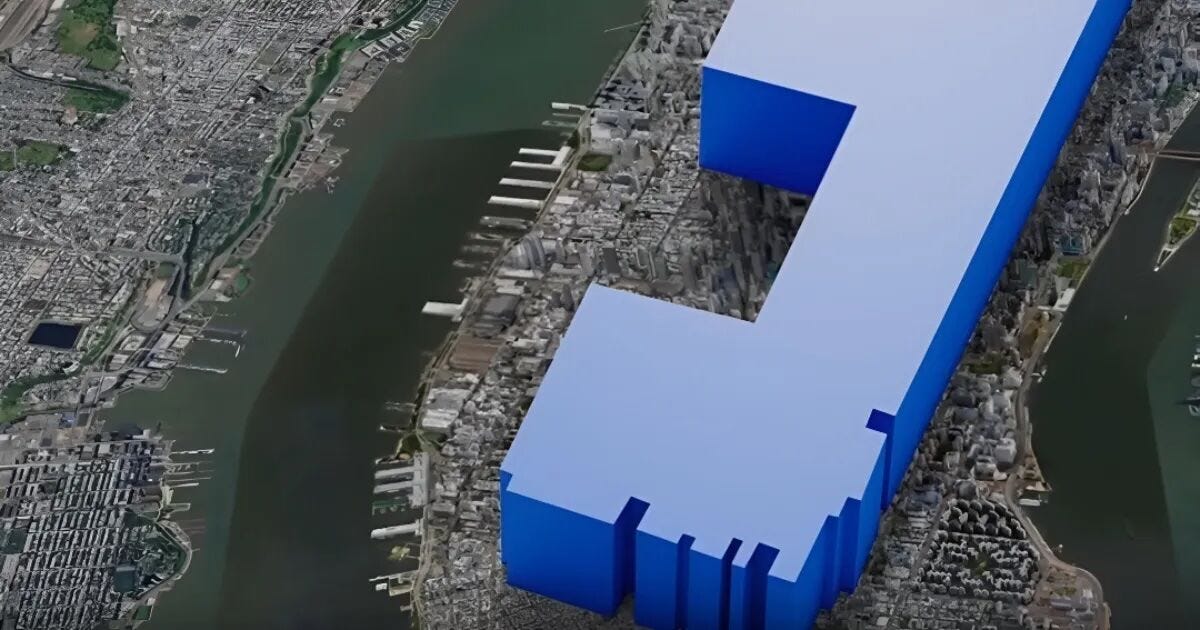

The image of Meta’s proposed Hyperion Data Center crushing Manhattan

Lord Byron’s Luddite Song

Terms to dig (internet rabbit holes)

Symbolic vs. Connectionist AI

Right to repair

Luddite fallacy

Situationist International

The legend of Ned Ludd can be traced back to The Nottingham Review’s issue published on 20 December 1811.

hey tiffany! i would love to learn more about how you are using technology and restricting it; whether it’s your phone, the internet or any form of tech comsumption