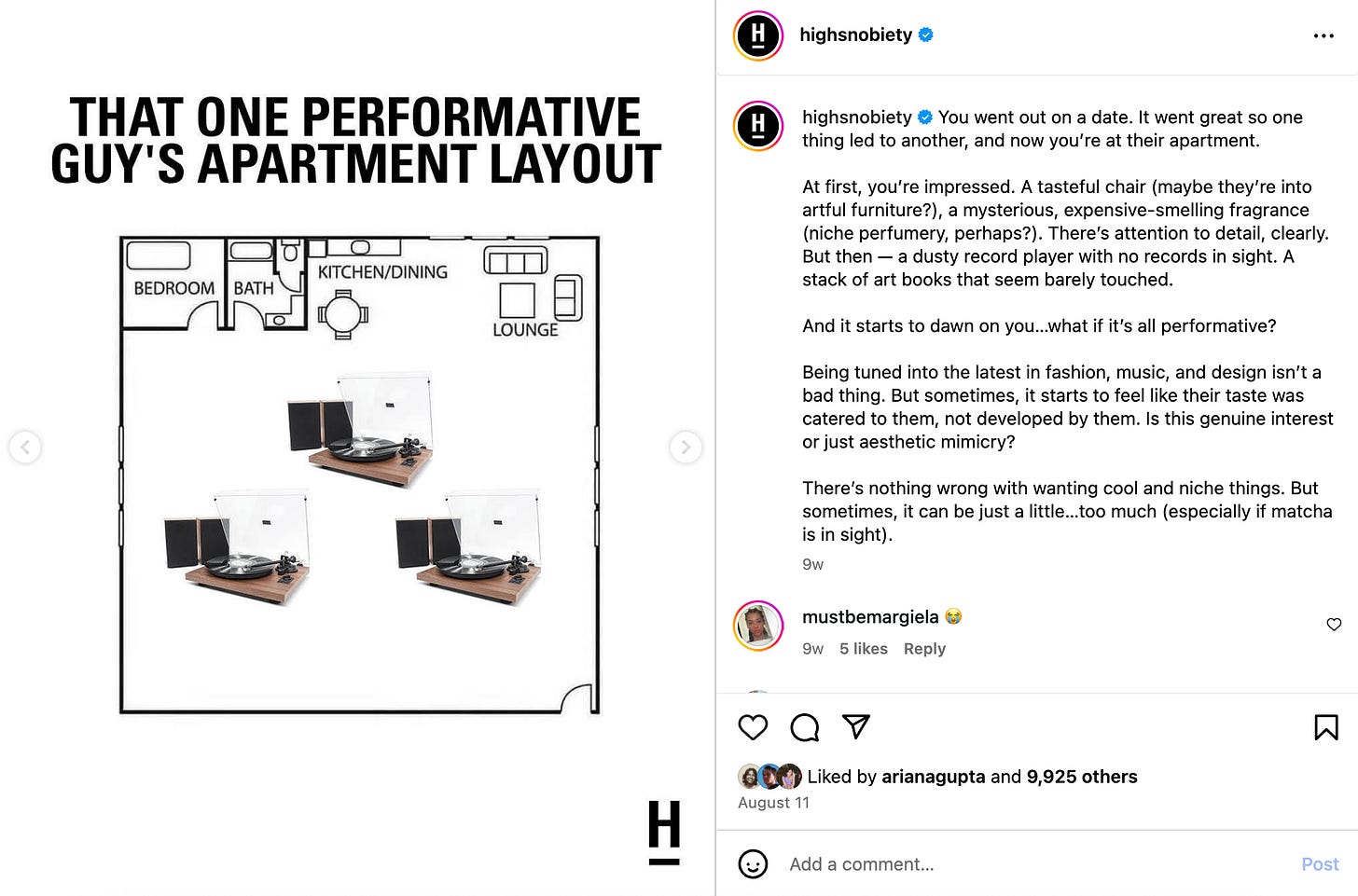

Performative bedroom decorating brought to you by Amazon Prime

Because our interests don't take physical form today, the intimate ritual of hoarding is now an avenue for performance.

This week on the intimacy of fandoms, bedroom CD collections, and the pre-Letterboxd era — how algorithms and Amazon Prime made the Performative Man.

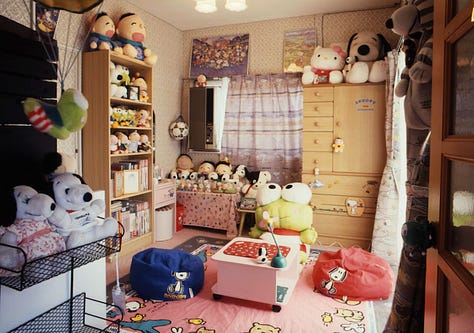

Adrienne Salinger’s series of teenage bedrooms from the 90s

I recently ended up in a hacker house housewarming in New York City.

The unit had it all: floor to ceiling windows, open kitchen, walk-in closets, an elevator that opened directly into the place. Even for New York, the rent was offensively expensive (I Zillow-ed the place, obviously). It was a unit that radiated the aura of Ryan Serhant.

Looking around, I saw whiteboards everywhere riddled with AI app ideas. A rogue (what I assume to be a knock-off) Mario Bellini couch sat next to a dozen Amazon desks, as though the five startup bros that lived in the unit gave up after someone decided to blow the entire furniture budget on one couch.

Upon doing my due diligence and (respectfully) snooping into each bedroom, what really struck me was the distinct, cookie-cutter aesthetic exhibited in each room. You have the Quentin Tarantino film buff who relentlessly quotes In The Mood For Love… the Clairo fanboy who drinks blue mountain espresso while playing the guitar.

Each tenant desperately wanted to be seen. You’d imagine these personas took years to develop. But, judging by the avalanche of Amazon Prime boxes sitting next to the stairwell, these personas seemed to have been purchased last week — when the tenants moved in.

Personality as a game of dress-up

Like Japanese modular pre-fab homes, personality (or the exhibition of one’s interests) has become a game of mix and match.

Algorithms have codified (virtue signals) commodities as performative starter packs while entire subcultures are reduced to permutations of hyper-specific items. All you need is a pair of wired earphones, a canvas tote bag, and a matcha in hand to convince the world of your sensitivity.

The fire to this gasoline-soaked state of culture is Amazon Prime and its incredible promise of 2-day shipping. For only $14.99/month, you harness the power of switching up your entire personality every two business days.

Amazon has blessed us with the ability to conform to trends in real time (even if it means wearing Temu’s version of Steve Madden’s version of the Ganni buckle micro-trend shoe). Our impulse purchases pay off in its incredibly short windows of relevance.

People say money can’t buy taste. But when taste has been watered down to a check list of five algorithmically-approved items, does that statement still ring true?

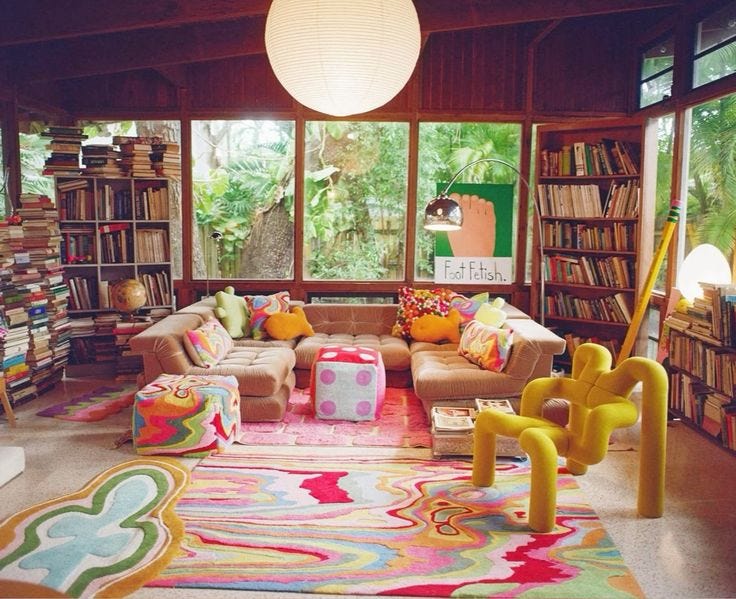

Cottage-core-maximalism might be the new millennial grey — see Dani Klaric’s work

Exhibiting one’s interests is the Gen-z mating call.

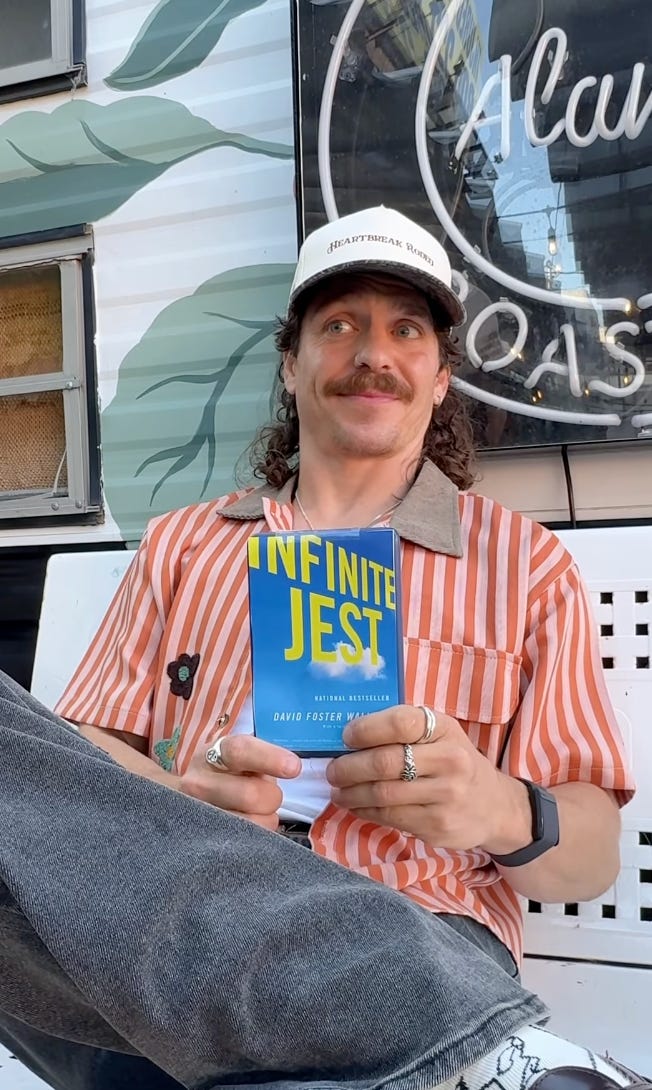

Performance, as TikTok has re-defined it to be, is the close relative of aura-farming. In this trend cycle, what anoints your manhood is reading Infinite Jest. Last week, a friend sent me a reel of someone printing out the cover of Infinite Jest and taping it on the back of his Kindle — just to make sure his endurance of DFW’s winding prose would be rewarded by a lingering glance from an attractive stranger.

I see you, intellectual. The truth will set you free.

The explosion of Spotify wrapped dupes, the return of Letterboxd, even your Substack reading lists all put your interests on full display — doing what Zuck originally wanted to achieve with Facebook’s Interests page. The stuff we consume is always being watched, so it only makes sense that it becomes an avenue of performance.

(Not that you asked, but I joined Letterboxd in 2014 and have since been locked out.)

Fandom used to be a much more private affair

Getting stuff used to be much more difficult. Acquiring a limited-edition band tee from that one concert required either your attendance or proximity to someone who did. Today, with abundance access to the internet, it’s only a matter of how much you’re willing to bid on eBay.

Two weeks ago I wrote about the intimacy of physical media. How the digitization of everything deprived us of touch and why the consolidation of all our interests into a sleek, frictionless screen is fueling our global loneliness epidemic. What I missed, however, is how we actually used our media: we read the magazines we spent all our allowance on. We wore out our CDs and cassette tapes. I could tell from the creases of my childhood paperbacks which chapters captivated me the most.

Today, “Cluttercore” is a trend that’s taken over the world of interior design. It’s fashionable to love a controlled, lived-in look. But before this movement of contrived staging, bedrooms were messy because their tenants were messy and hoarders.

Sofia Coppola’s films perfectly captures this aesthetic (and has since become a TikTok trend). Claire Marie Healy’s book on Girlhood outlines the evolution of this form of lived-in-ness through works in the National Collection of British Art. My personal favourite, Japanese photographer Kyoichi Tsuzuki’s early 2000s cult photo series on the bedrooms of Tokyo’s most devoted fans, candidly captures the intimate extremes of personal obsessions.

Our fixations on things used to be more pure —in part because we had so (comparatively) much less. There was less to buy and no one was watching. We were free to obsess over whatever we wanted.1 In the absence of social media and the entire premise of online-virtue-signaling, there was arguably less of an effort to align your interests with what was fashionable then.

Letting someone into your space in the 90s made you incredibly vulnerable. With the cost of each CD, DVD, book — you had to put your money where your mouth is. Sure, you could rave about your fascination with Jazz, but when given the choice, are you spending $17 (this was NOT adjusted to inflation) on Leonard Bernstein’s concert recordings or the NSYNC album you actually want? Visitors were looking directly into your most protected core.

“Cluttercore” feels contrived because our interests don’t have to take physical form today. With streaming and smartphones, you can choose what to display vs. what to consume — making physical media less functional, more decorative (performative).

Remember Lane’s iconic hidden CD collection in Gilmore Girls?

They were just trying to get laid

Back to the hacker house. Let’s cut them some slack — can’t blame a guy for making an effort.

None of this is to say that our interests are entirely driven by perception today. But when everything lives on our devices, physical media becomes decoration and decoration inevitably invites curation. These poor guys are just trying to get laid with five (albeit clashing) algorithmically-approved notions of ‘style.’ They were, in all honesty, lovely hosts.

In our current obsession with individuality, it seems there are still invisible boundaries of what’s en vogue. The way we purchase new personalities is not much different from how we purchase our Halloween costumes, and in the spirit of this spooky season, may this post inspire the most off-kilter costume of it all.

Last year, I went as a finance bro from Tinder, holding a fish.

Hello friends! I recently enabled paid subscriptions to support some of my more rogue ventures in cyber celibacy (typewriters, building a printing press… more to come).

I also created a Snail Mail Membership, where (in true neo-luddite fashion) I’ll physically mail you this newsletter on a bi-monthly basis. For the first dozen snail mail members, I’ll handwrite your first letter <3

We can still obsess in the comfort of our own spaces today, but there seems to be more of a cultural push to exhibit ourselves.